One of the most common objections we face at SARCRAFT when promoting our courses is the question, “Why do I need to know this?” Or, similarly, “I hike, but I don’t really go into the wilderness.” “I only go on day hikes.” “I only go out in the woods in good weather.” Their assumption is that most of the time, nothing bad will happen. Most of the time, they’re right. They think it won’t, until it does.

Even among those of us who are preparedness-minded and practice defensive living (which I would assume is most of the readership of this blog), I think there’s always the question of “Am I ever really going to use these skills?” Unless you’re an outdoor professional who intentionally puts themselves outside in nasty weather and dangerous places, it’s easy to slip into the mindset of “The odds are so low – that’ll never happen to me.” You think it won’t, until it does.

Because of being in search & rescue and spending months on the Appalachian Trail, I’ve probably had to use survival and self-rescue skills more than the average person who ventures outdoors. I don’t say this to brag, I say this as an example that yes, these situations really do happen to real people. And each time, with a handful of exceptions, I didn’t see it coming. Many times, the situation that turned dire was the last one I ever expected to. I’ll use one as a case study today.

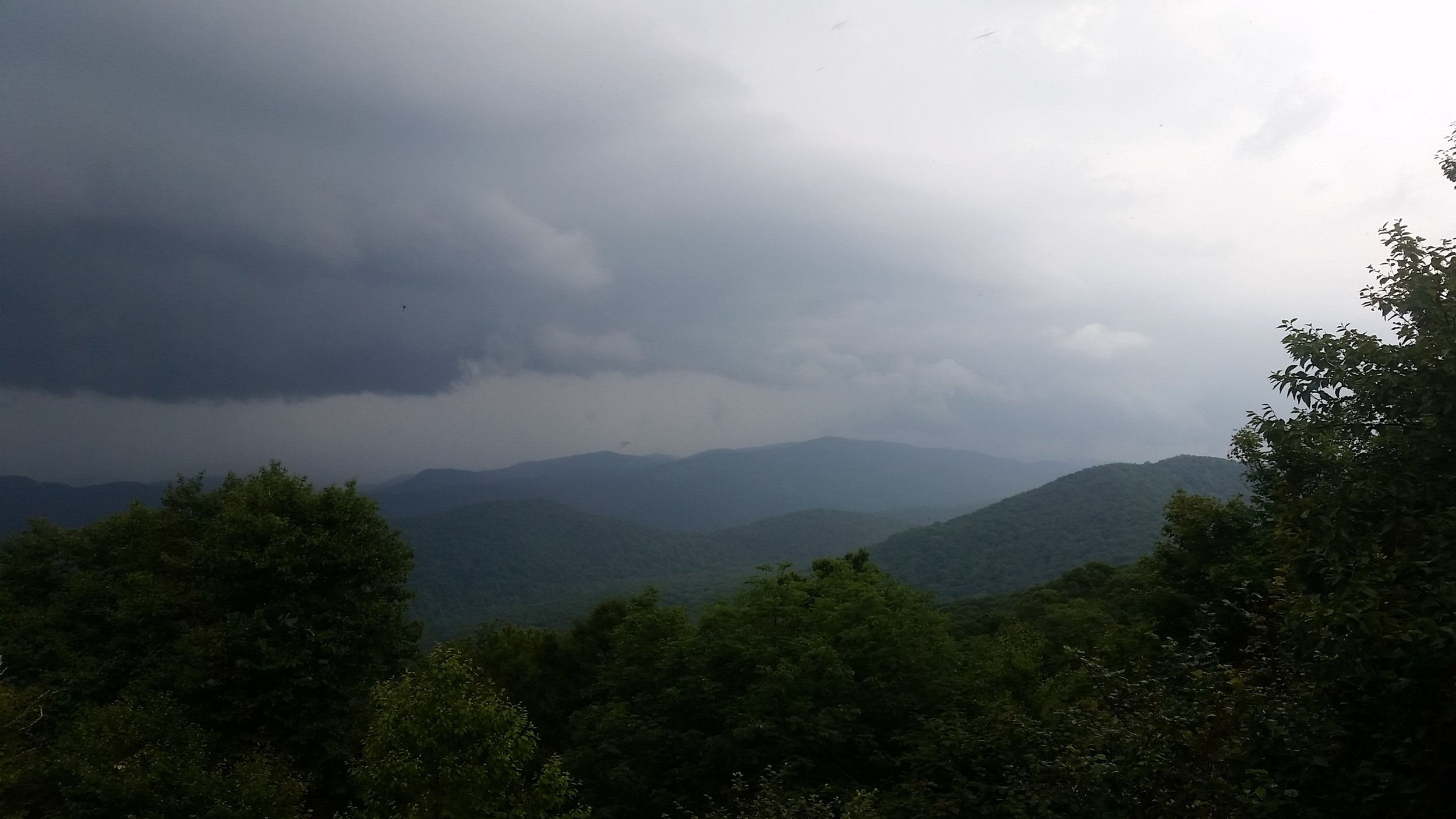

July 27th, 2016. I had spent most of a hot, soupy day climbing a steady ten-mile grade up the side of Bald Mountain on the Virginia Appalachian Trail. I’d been watching an enormous thunderstorm build for hours over the horizon, slowly inching its way closer. I figured I would probably reach the top of the mountain just as it hit, and I was right.

Torrential rains came driven by 30mph+ straight-line winds. Lightning crashed close by, and I was thankful when I crested the mountain and got down lower into the trees. The worst of the storm passed in about twenty minutes, and a steady rain set in for about an hour. The biggest thing I noticed was the sharp temperature drop. It had been hovering around a hundred degrees for most of the day, and now was about fifty. I’d sent my rain gear home a few hundred miles earlier, and the shower was a welcome break from the heat wave I’d been hiking through for days.

I realized the rain wasn’t going to stop, so I pulled into the nearest trail shelter a few miles further on down the way. For those of you unfamiliar with the AT, these are basically small wooden Adirondacks with three walls, a roof, and a floor. The rain had slowed to a slight drizzle, and I sat down on the edge of the shelter to take a load off. As I sat, it occurred to me how cold I was getting. Although the rain had nearly stopped, the clouds were still heavy and there was a stiff breeze blowing, and it hadn’t warmed back up at all. I started to shiver, and shed my pack and wet shirt. I started to unpack and get set up for the evening, but the shivering didn’t stop. In fact, my fingers and toes started to feel numb. The more time passed, the harder it was to concentrate on the task at hand. I felt lethargic, and all I really wanted to do was lay down. I chalked it up to the long day on the trail.

I sat back down and stared at the dirt. Then it hit me. Hypothermia. I stripped naked and did about fifty pushups to get my circulation going again, and then set to building a fire. There were dry leaves and twigs under the shelter, I used this plus a few pages out of my journal to get a fire going. The fact that there was no dry wood to be had didn’t help, but I made it happen. I dried myself out, followed by my clothes. I got dinner cooking, put on my dry clothes and a light jacket, ate, got in my sleeping bag, and was fine. (Some of you may ask why I didn’t just get in my sleeping bag to begin with. It was a +65 ultralight and wouldn’t have been able to get me warm enough quickly enough.)

Hypothermia was just about the farthest thing from my mind in late July, when I’d been trying to stay cool and avoid heat exhaustion a few hours before. Seriously, who thinks of worrying about death from loss of core temperature in the middle of a heat wave? But the conditions were just right, and I didn’t expect it. I knew this could happen in theory, but normalcy bias set in and it didn’t cross my mind until it was staring me plain in the face. I didn’t think it would happen, until it did.

Most people don’t really want to believe that they could be faced with a dangerous, or even deadly, situation when they step outside to enjoy the outdoors. And statistically, they’re pretty right. This isn’t the frontier. The world we live in, even our wilderness areas, is so much tamer than it was even half a century ago. Cell phones and widespread coverage have made calling for help a real option in a lot of places where even twenty years ago you would have been on your own.

But while the numbers will tell us that we’re statistically safer than we’ve ever been, the numbers also tell us that there are exceptions. There are still wild places where no cell tower will penetrate if you need to call for help. Bad weather is still bad weather. Some terrain is just inherently dangerous. Every once in a rare while, wild animals really do attack people. These are all things that really can lead to grave injury or death, if you aren’t prepared to face them.

But that’s part of the glory of wild places. They’re just that: wild. The safest way to avoid hypothermia and heatstroke, loose rocks and high cliffs, aggressive bears, rattlesnakes, and electrical storms, is to simply stay inside. But there’s so much loss that accompanies that decision. You’ll never experience the grandeur of a mountain view that no road reaches, or the inexorable power of a wild river. You’ll never see animals in their home, untainted by human presence. You’ll never experience the freedom that comes with leaving most of your possessions behind and living close to the land.

So what’s the solution? It’s twofold, and it’s simple. Educate yourself, and cultivate a mindset of preparedness. Learn the basic skills needed to survive when things go south. Firecraft, water procurement, and basic sheltering. Basic first aid and CPR. How to start a fire in the rain. How to recognize and treat heat and cold related injuries. How to navigate with and without a map and compass. How to read an ornery bear. What to do if you fall in a river, and so on. And then practice them. Learn them, and get good at them.

Secondly, cultivate a preparedness mindset. Start practicing situational awareness, so you’re ahead of the curve when conditions go from normal to scary. Become more present and less complacent. Read case studies about bad things that could happen in activities you like to do, and then mentally plan for them. Do things that challenge you, and expand your comfort zone. Carry a modicum of necessary gear every single time you go out, whether you think you’ll need it or not.

If you practice these two things, the darkest days and direst of circumstances can be just another part of the story of your adventure. Fear will have no place in your heart when you venture into the wild, and come what may, you can stay the course and prevail. Because if you spend enough time in the wild places that feed your soul and make your heart come alive, things will happen. And that’s okay, because you’ll be ready.

- Alex